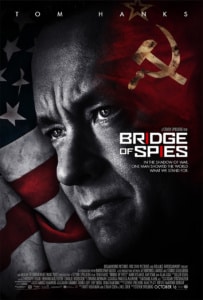

Review: ‘Bridge of Spies’ and Frank Meehan – John Winter (CHS Former Staff)

In the extremely entertaining and tense Cold War thriller Bridge of Spies, directed by Steven Spielberg and released in 2016, Tom Hanks plays a savvy New York insurance lawyer called James B Donovan who, in 1957, is plucked from relative obscurity by the US government to defend a captured Soviet agent, Rudolf Abel, in a high-profile spy trial in 1961. Rudolf, who went by a number of different names in the US, including William Fisher, was the most senior undercover Soviet agent working in North America from 1948 to 1957. His trial in the US was the year the Berlin Wall was built by the East German Government; the divided city is the backdrop for the main action in this film.

Bridge of Spies is based on a true story, which Spielberg stumbled upon in the form of a script by a British writer and revealed; “It’s a singular incident that has remained kind of… I wouldn’t call it a secret, but it’s not been dealt with or talked about much.”

The incident which Spielberg is referring to took place in 2 places in Berlin on Saturday 10th February 1962. It was recorded – by the only journalist present, Annette von Broecker, who managed to get herself to the first location at Glienicke Bridge – as a kind of spy swap between the Americans and the Russians that had not been tried before: the two protagonists (the Russian spy Abel and Gary Powers, the pilot of the U-2 spy plane shot down over Russia nearly two years earlier) had to be brought to the same place at the same time and bartered with utmost care under the quiet gaze of snipers on both sides hidden in the nearby forest. The second incident is at Checkpoint Charlie back in the city centre, at the same time.

The two men at the centre of the now famous Glienicke Bridge exchange are Donovan, who defends Abel – when the whole of America thinks Abel should be executed – and Wolfgang Vogel, an East German lawyer who served as a go-between wearing not two hats but three; he negotiated with Donovan while working with the East German Stasi and the Russian KGB. Vogel is described in the book Bridge of Spies, by Giles Whittell, as a man with “the highly sensitive antennae of a natural deal maker” as he brokers the exchange that day on Glienicke Bridge in Berlin. Vogel went on, in due course, to persuade the West German government to part with 6 hundred million West German Marks for the freedom of nearly a quarter of a million people behind the Iron Curtain, between 1962 and the eventual collapse of the East German state with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989.

The elements of mistrust and even dislike between Donovan and Vogel are striking features of the film. Vogel is not depicted as any kind of hero, in stark contrast with Spielberg’s depiction of Donovan who is a firm believer in due process and the constitution. Donovan’s role as defender turns both him and his family into targets of hatred for the American public. In the film, he waxes lyrical about the near-mythical power of the US constitution to anyone who will listen – judges, lawyers, CIA agents – until they can quote his catchphrase off by heart (“Every person deserves a defence! Every person matters!”). In many ways, Hanks plays the ultimate good guy under intolerable pressure both from his compatriots and from their enemies; the quiet suburban American who sets out to understand and then improve the world beyond.

Spielberg also plainly admires, perhaps loves, the Abel he has created. Without being unpatriotic or compromising his distaste for the Soviets, he introduces a moral equivalence between Abel and Donovan. They are both brave men fighting for something; though, in the case of Abel, played by Mark Rylance, what that is remains enigmatic.

Kevin Maher hit the nail on the head with his review about the film in November 2015 when he wrote; “This is all lovely. But it’s also a shame. Because there is a brilliant, exemplary movie in Bridge of Spies that is struggling to get out from underneath a bucket of schmaltz.” The real Donovan was an experienced naval intelligence officer in the Second World War, who became a serious player in the espionage community – a natural choice for the Abel gig, and someone who, one suspects, achieved results through dreary old hard work and professionalism. More importantly still, the third person involved in the exchange between the Americans and the Russians on that snowy day back in February ’62 – this time at Checkpoint Charlie – is just as interesting and certainly deserved to be far more than just an incidental sub-plot in the film. His name is Frederic Pryor and his saviour is a fascinating Scotsman, born in America, named Frank Meehan. They deserve a film or a TV series of their own.

Captivated by the story of Pryor in the film, I decided to find out more about his real-life story. Frederic was a twenty-eight year old Yale Postgraduate student, who had been interrogated by the Stasi (East German Secret Police) every day for the preceding five months before his release at Checkpoint Charlie in the centre of Berlin on 10th February 1962 on suspicion of espionage. Frederic was a bright student with an enquiring mind and a serious case of wanderlust. He was entirely innocent and it was a worst case of being in the wrong place at wrong time. Driving around Berlin in his red VW, he became trapped in East Berlin when the wall, that subsequently divided the city for nearly thirty years, began to be erected on 13th August ’61.

The key unresolved issue in the film is, therefore: while Donovan, acting for the Americans, was busily securing the release of Powers, who else was involved with the release of Pryor? A second key question was why did the Americans almost risk everything to secure the release of Pryor (in a two for one swap) when he was of no obvious value politically. The common link on the German side was clearly Wolfgang Vogel who negotiated the safe return of both Westerners. As I researched further, one key character emerged who is not featured in the film: Frank Meehan, the man who eventually struck up a friendship with Vogel which was to last more than thirty years – and whom I later found out is closely connected with one family whose son is in the Sixth Form at Cheadle Hulme School – was the other hero for the Western Allies that day. Meehan secured the release of Pryor with Vogel at Checkpoint Charlie, while Donovan exchanged Abel for Powers at Glienicke Bridge.

Determined to find out more and having been provided with a personal lead to ninety-two year old Frank, who lives just north of Glasgow, I have been able to piece together the missing parts of the jigsaw, sadly left out of Spielberg’s film. Starting through email and then culminating in a visit to interview the amazingly modest and articulate Frank at his home in Scotland, these are the answers to some key questions, which shed some light on Frank’s involvement that day back in snowy Berlin in early 62:

How did you, a Scotsman, born in New Jersey, become so proficient in speaking German and Russian in the 1930s?

I did German at school in Dumbarton and then at university (in Scotland); I was then a GI in Germany after the war and a clerk in the American Consulate in Bremen 1947-48. The Department of State assigned me to Russian Language and Area Studies in Washington and at Harvard 1956-57. I was a Political Officer in the American Embassy in Moscow between 1959 and 1961.

How did you come to be posted to Berlin in the Cold War period?

The posting to Berlin was a normal Foreign Service assignment following my tour in Moscow.

How long did you eventually spend in Europe between 1961 and 1989?

I spent the period between 1961-66 in the US military government mission in West Berlin, as a political officer working on the GDR. Getting away for some time from Berlin, but still close to German affairs, I was Political Counselor in the American Embassy in Bonn 1972-75 and Deputy Chief of Mission in Bonn 1977-79. I then became the American Ambassador in Prague 1979-80, and Ambassador to Poland 1980-83. My final assignment before I retired in 1989 was as Ambassador to the GDR 1985-88.

How cold and how dangerous was it in Berlin late January 1962?

It was cold enough, but not particularly dangerous for people like myself working under the usual rules of diplomatic practice.

What part did you play in the case of Frederic Pryor after the Russians picked him up? Why did the filmmakers leave you and Pryor’s parents out of the film?

I was the Pryor family’s main contact with the US Mission Berlin, and I was in close touch with the East German attorney, Wolfgang Vogel, whom Pryor’s parents hired to represent him. I guess Spielberg left Pryor’s parents and me out of the film because what we did wasn’t so much of a story at the time in a way, and perhaps didn’t have as much drama in it.

What sort of character was Pryor and what are your abiding memories of 10th February 1962?

I never actually met Pryor until the day of his release. I had to rely on Wolfgang Vogel for updates on his well-being in captivity. No money changed hands to secure his release; Wolfgang certainly did not receive a nickel for all the private work he did to secure the release of the Yale student, either from Pryor’s parents or the US Government. The one thing that struck me was how unemotional he was in the car after Vogel delivered him to me. There were no histrionics while we waited more then thirty minutes for the go-ahead from Glienicke Bridge to drive off to see his family who were in West Berlin.

How much were you acting for the Pryor family and how much for the US Government?

I was working only for the US Government. The Pryors were an American family who turned to the US Mission Berlin for help, and the Mission assigned me to help them any way I could.

How was it you found you could trust Wolfgang Vogel in Berlin? Was your shared Catholic faith important? What else did you have in common, which meant that you could get along so well with each other?

It took time for Vogel and me to get used to each other. Right from the start, though, when we met in his office in East Berlin, he struck me as someone who could and would think and talk for himself. That in itself was unusual in those days. As time went on I found that he talked straight and kept his word. Our being Catholics was interesting, but not crucial. The main thing we had in common, I think, was that we both thought it right to stress the positive and avoid ideological debate. Vogel was good in personal relations and knew how to put you at your ease. I tried to meet him half way. We remained lifelong friends and I attended Wolfgang’s funeral many years later in 2008 in Bavaria. I will always be grateful for the fact I visited him with my daughter just before he died when we remembered with fondness our times back in Berlin at the height of the Cold War conflict.

How did Vogel seem to gain the trust of West Germans, East Germans and the Russians?

Vogel had close ties to East German security and intelligence and was subject to their guidance and control. The West Germans learned from experience that he could deliver on issues that were important to them, principally the release of prisoners held in the east and the reunification of families. I imagine – but I am largely guessing here – the Russians found he was useful to them in prisoner exchange cases.

How much contact did you have contact with Donovan in Berlin? Is it true that Donovan did not seem to like Vogel? Why did you trust Vogel so much when Donovan didn’t?

I did not have any contact with Donovan in Berlin – or elsewhere. Donovan’s treatment of Vogel in his book, Strangers On A Bridge, is negative, certainly giving the impression he did not like Vogel. Donovan dealt with Vogel only in the Powers/Abel/Pryor case so far as I know. Donovan could not speak German and had to use an interpreter Duane Bruce in his dealings with Vogel. I got to know Vogel over a much longer period involving a number of prisoner release or exchange deals – from 1961 until the Shcharansky deal in 1986, and beyond, until Vogel’s death in 2008. I learned from experience that I could trust him to act responsibly.

How many prisoners were you and Wolfgang able to release altogether?

Thousands of exchanges took place altogether right up until 1989. Wolfgang was the leading player and negotiator in all of these on the Eastern side.

What contact did you have with the KGB i.e. Drozolov and Shishkin?

I had a phone conversation with Ivan Shishkin when Donovan was in Berlin before the Powers-Abel exchange, and I met him some months later at a (British) cocktail party in West Berlin. He struck me as quick and smart – with very good English, as I recall. Ivan was also someone who made a positive impression on me at the time, not least because his English was so fluent.

How important were the East German authorities, with men like Streit, and how much were they just puppets in the hands of the Russians?

If we are talking about how important they were to us in cases where they had detained/imprisoned US citizens, the answer is: important. We had to deal with them, not directly since there were no diplomatic relations between us, but through people like Vogel who knew their way through the East German system. The Soviets were in charge of East Germany in broader political (and military) terms. When they withdrew their support in 1989-90, the East German system quickly collapsed.

How close did the whole deal come to collapse, as depicted dramatically in the film, with pressure being exercised by Donovan?

I think you could argue that Donovan’s pressure, for instance that Pryor’s release was a US objective, was a major positive factor. You could argue further that it was Soviet pressure, arising from Donovan’s exchanges with them, that made the East Germans release Pryor although they were getting nothing in return. Interestingly, events in the film are not quite correct at the climax of the story: Frank and Pryor have to wait more than half an hour for the signal that the exchange at Glienicke Bridge has taken place, rather than the other way round.

How did you feel knowing that you could be attacked or arrested at any time in Berlin (without US protection)? Did Donovan actually get attacked on the streets and have his coat taken? Did Vogel get pulled over for speeding as in the film?

I don’t remember worrying about being attacked or arrested – but then I did have the protection that being a US diplomat carried with it. That didn’t mean you couldn’t be involved in unpleasant incidents, but I never was involved in fact. I don’t remember ever hearing that Donovan was attacked in the street or had his coat taken, or that Vogel was pulled over for speeding. This presumably is another example of poetic licence by Spielberg.

What was the press coverage like at the time in America or Germany?

The exchanges were carried out in secret on the day. There was one Dutch journalist, Annette von Broecker, who was able to interview a policeman who had witnessed events at the Bridge and was prepared to talk; she filed her copy that then made the headlines in the West in the days after the release of both Americans.

Why was Wolfgang Vogel imprisoned in Germany after Reunification on 3rd October 1990?

He was arrested on “conflicts of interest”. He was not asked to pay tax on the money he made from exchanges by either the West Germans or East Germans. He was found guilty in court, but was released on appeal after just six months. I wrote to the State Attorney on his behalf.

Did you ever try to see your Stasi file after the fall of the Berlin Wall?

I have never tried to see my Stasi file, which I imagine has stuff in it I’d be interested in. I think, though, it would be a mistake to try and see it now.

How important have foreign languages been in your life?

I am just learning Spanish now in my nineties because I have grandchildren living in Mexico. I still read in French and German and I can speak Russian and Hungarian from my time working there. My favourite city in Germany is Bremen. The most interesting city in Europe remains, for me, Berlin, because it is a city that is forever changing; this, together with its central role in shaping 20th Century World History, adds to its obvious charm and appeal.

As a postscript, the enduring friendship between Frank and Wolfgang, which starts when they are on opposite sides of the wall in the Cold War and survives the transformation in Europe of German reunification, is a human-interest story fit for a wide audience. Having been bombed out in his family home in the Clydebank Blitz in the Second World War, Frank Meehan was evacuated as a child. However, he never harboured any personal grudge against the Germans. On the contrary, he decided to study French and German at university in Glasgow, with a view to using his languages in his working life. Little could he have imagined where that would lead. The very fact he could speak German in East Berlin with Vogel meant two vital things: he came to understand properly the man for who he really was; and he was able to build the level of trust needed to secure the release of Pryor. Donovan’s part in the Bridge of Spies is not to be underestimated, as acknowledged by Frank himself, but this excellent film is definitely somewhat the poorer for ignoring the latter’s vital contribution to events which were of world significance back in February 1962.

Former Second Master, John Winter